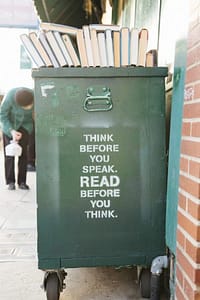

This is probably the most common writing advice. If you haven’t heard about it, you will now – it’s everywhere. But what is it?

What is it?

Showing describes details, actions, or images so reader can recreate and imagine the story and characters in their mind. I prefer to think of this as describing, for example, how a character feels instead of explaining that she is sad.

Russian novelist, Anton Chekhov, said it nicely in this oft-quoted line:

“Don’t tell me the moon is shining, show me the glint of light on broken glass.”

Why do we want to show?

Readers are more likely to be more immersed, involved, and active when we show (describe) because the descriptions and imagery can arouse visceral feelings, bringing the reader into the story. It can also make characters feel more real because readers will be able to relate to what the characters are going through. For example, we can connect to a character’s fear of heights when the character’s knees tremble, his heart rate drops, and his mouth becomes dry. However, if we simply explain that the character is afraid of heights, the reader will understand the point intellectually but won’t necessarily be absorbed into the story.

How to show (describe)?

1. Provide details when describing both character and setting

For character, instead of writing that the woman was tired, it would be better to describe her stooped posture, sunken eyes, or lifeless eyes. For setting, instead of writing it was a busy office, describe how the photocopying machine was working at full speed, the dozens of people rushing from one desk to another, or the overlapping conversations that each staff is having with each other.

2. Show it in the character’s response

Instead of telling us that the man was emotional, describe his red eyes holding back the tears. A character’s can also be in dialogue, thoughts, feelings, body language. A curt response show that the man was rude or condescending.

3. Avoid words related to emotions, such as happy, sad, angry…

…as you’d simply be telling (explaining) things to the reader. Instead, you should describe the feeling of being happy, sad, angry. For example, for happy, it could be the character’s eyes popping out in a circle, fists pumping in the air, or the grin across the face, etc. A good test is to ask yourself, “how do we know” that a character is happy, sad, or angry?

4. Use all five senses.

Don’t forget to describe using our five senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste as telling only offers one dimension.

When to show (describe)?

Showing (describing) should be used to create atmosphere, increase tension, or provide a deeper understanding to a character and ultimately create a vision in the reader’s mind so they can experience the story as close as possible to what the author had in mind.

As you may have picked up, showing (describing) generally requires more words but don’t use this to describe absolutely everything and be careful of rambling – you don’t need to show the minutest detail of everything; only the details to create the atmosphere, tension, character.

When to tell (explain)?

Before you show (describe) everything in your story, telling (explaining) is still important because you don’t need to show every single detail. Plus, sometimes, you simply need to have exposition to move the plot along.

1. Don’t convolute things to the point of being verbose, interrupting the reader’s flow

In this sense, understanding the purpose of the scene will help. Sometimes, the detail isn’t worth the long description and may slow the pace of your story, especially in an action sequences or emotional scene. For this simple example, you can write, “The girl slammed her fist onto the table” instead of “she slammed her fist onto the wooden plank that was propped up with four legs, one of each of the corners.” This is convoluted and unnecessary. Instead focus on the thing that you want people to take away.

2. Show throughout your story instead of info dumping

If your story contains a lot of detail that you need the reader to know, show pieces of information throughout the story rather than info-dumping at the time the reader needs to know. For example, if a character is suspected of having an affair, don’t wait until the third act to reveal the motivation of the character’s infidelity through long winded dialogue, instead pepper clues prior to that, such as the character coming home late, being rejected by their partner from any intimacy, or always texting on their phone. That way, you can ‘tell’ a shorter exposition when it is called for.

Showing (describing) vs telling (explaining) – a balancing act

There should be a balance between showing (describing) and telling (explaining). You don’t want bury the reader in long-winded descriptions if it is not important to the scene and you don’t want to ‘tell’ everything as it won’t be engaging for the reader. Another test is to play with both devices. If you can ‘tell’ the detail without losing much of the feeling, effect, engagement of the reader, or it doesn’t detrimentally impact the story, considering ‘telling’.